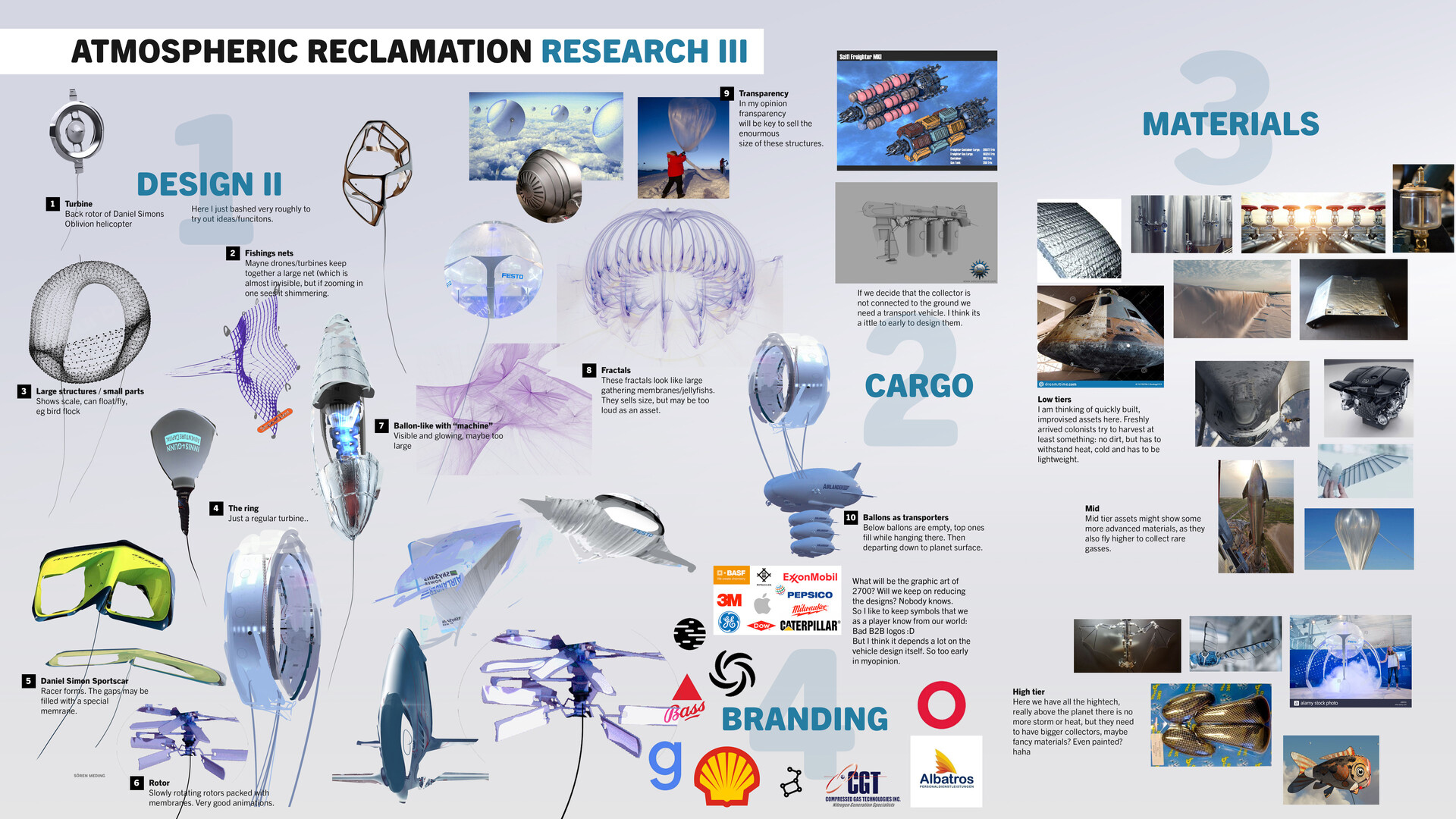

1. Research

I always start with broad, in-depth research, both to immerse myself in the topic and to explore a wide range of ideas. This approach also helps give the client an early sense of direction. Often, they already have something in mind, and this initial phase helps align our visions from the start.

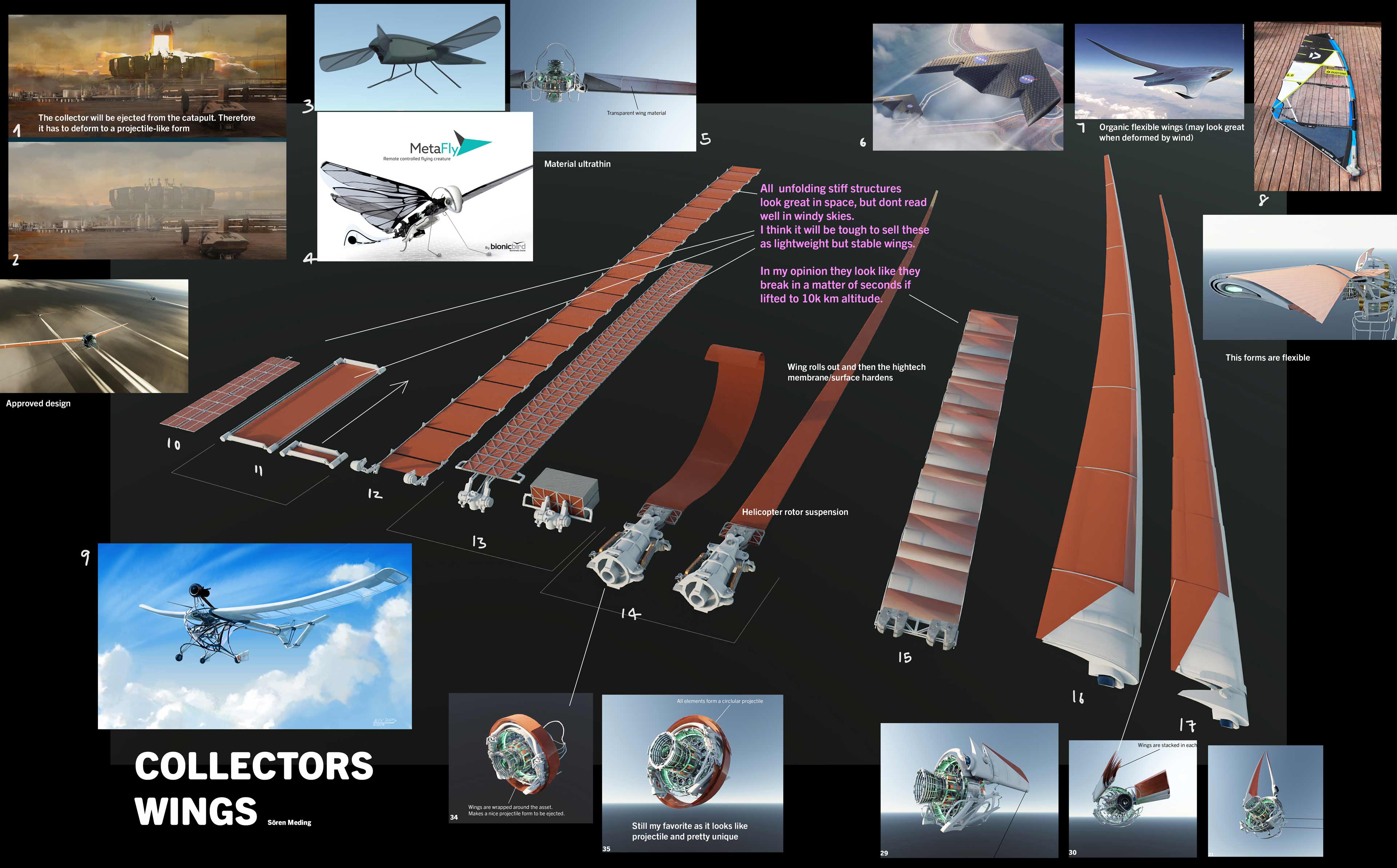

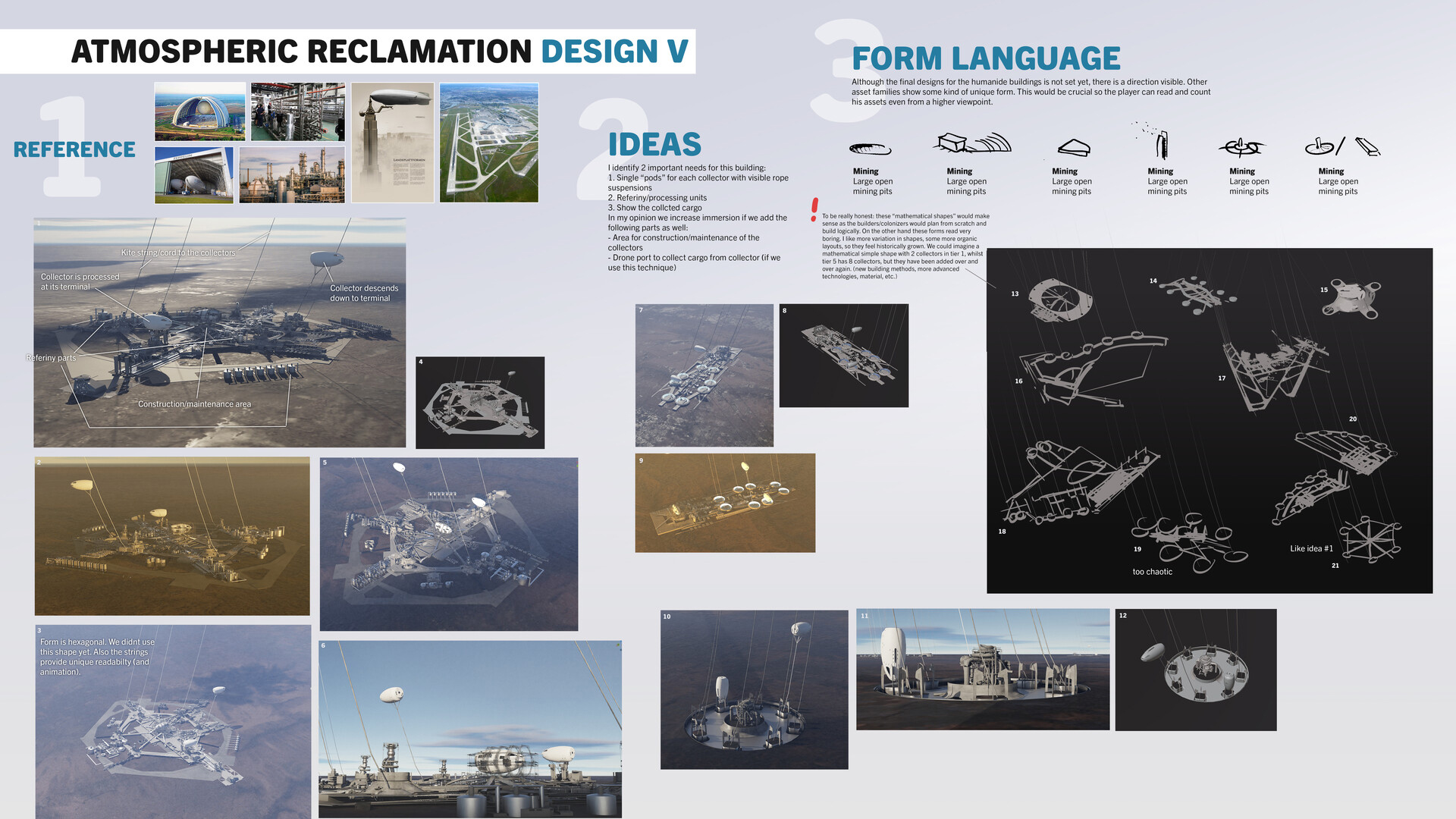

So, as seen here, should the Atmospheric Reclamation Unit be inspired by membranes, chemical processes, or vacuum cleaners? Or perhaps by flying turbines, condors, or albatrosses? Maybe even fishing nets, the wide-open mouths of whales, or balloons and zeppelins? Or should it feel more like a kite, riding the wind?

2. Photobashing

In parallel, I approached the topic from a visual standpoint, kitbashing and sketching to spark inspiration. I also began thinking through the logic of gas transportation: Should the kites be lowered once they’ve harvested enough? Should automated drones handle the freight transport? Or could there be pipelines integrated into the kite tethers themselves?

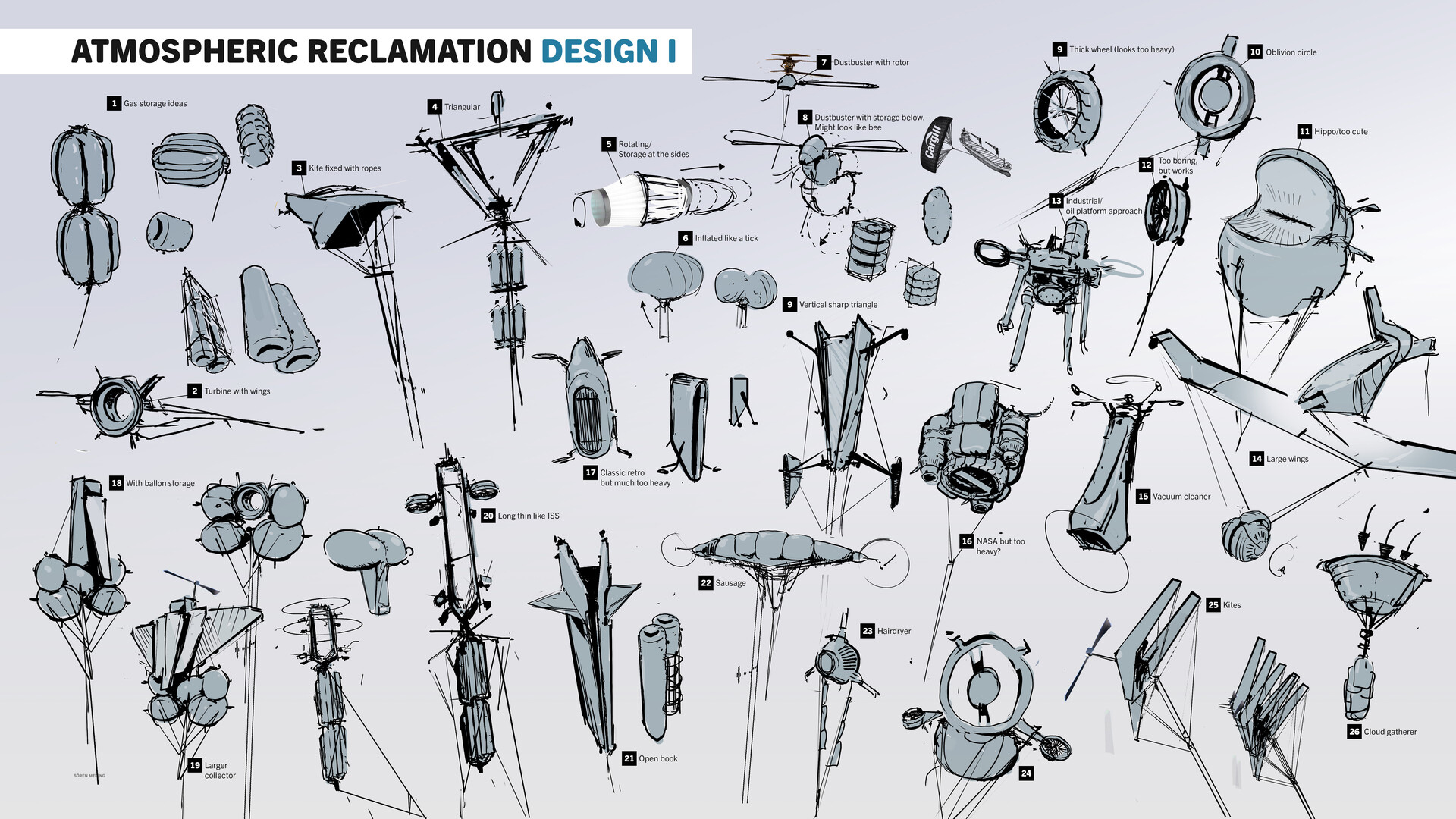

3. Sketching

Third: I began with a few sketches to streamline all the ideas I had in mind. I like to call sheets and processes like this “the buffet”, because it’s where you lay everything out and decide how much, and what, you want to put on your plate. Throughout production, I’ll refer back to this foundation “plate” and work my way through it, piece by piece.

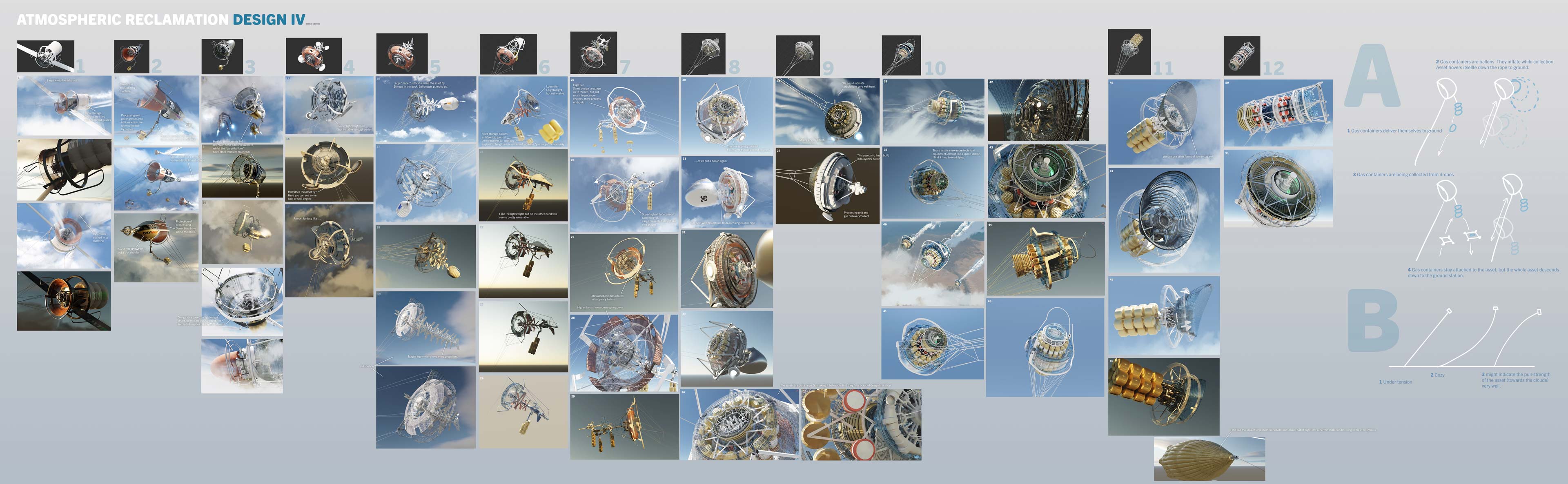

Translate into 3D

All three ideation methods are done—drawing, photobashing, and research. Now it’s time to move into 3D.

I’m already a bit worried there are too many ideas on the plate, the range of designs is quite broad.

On the other hand, if time and budget allow, I’d love to test all of them in 3D. In my experience, that’s where the happy accidents tend to happen.

But there’s a catch: it’s time-consuming, and it’s easy to fall for new favorites that weren’t part of the original idea. You risk drifting away from the core vision.

It’s a fine line to walk.

Stepping into 3D

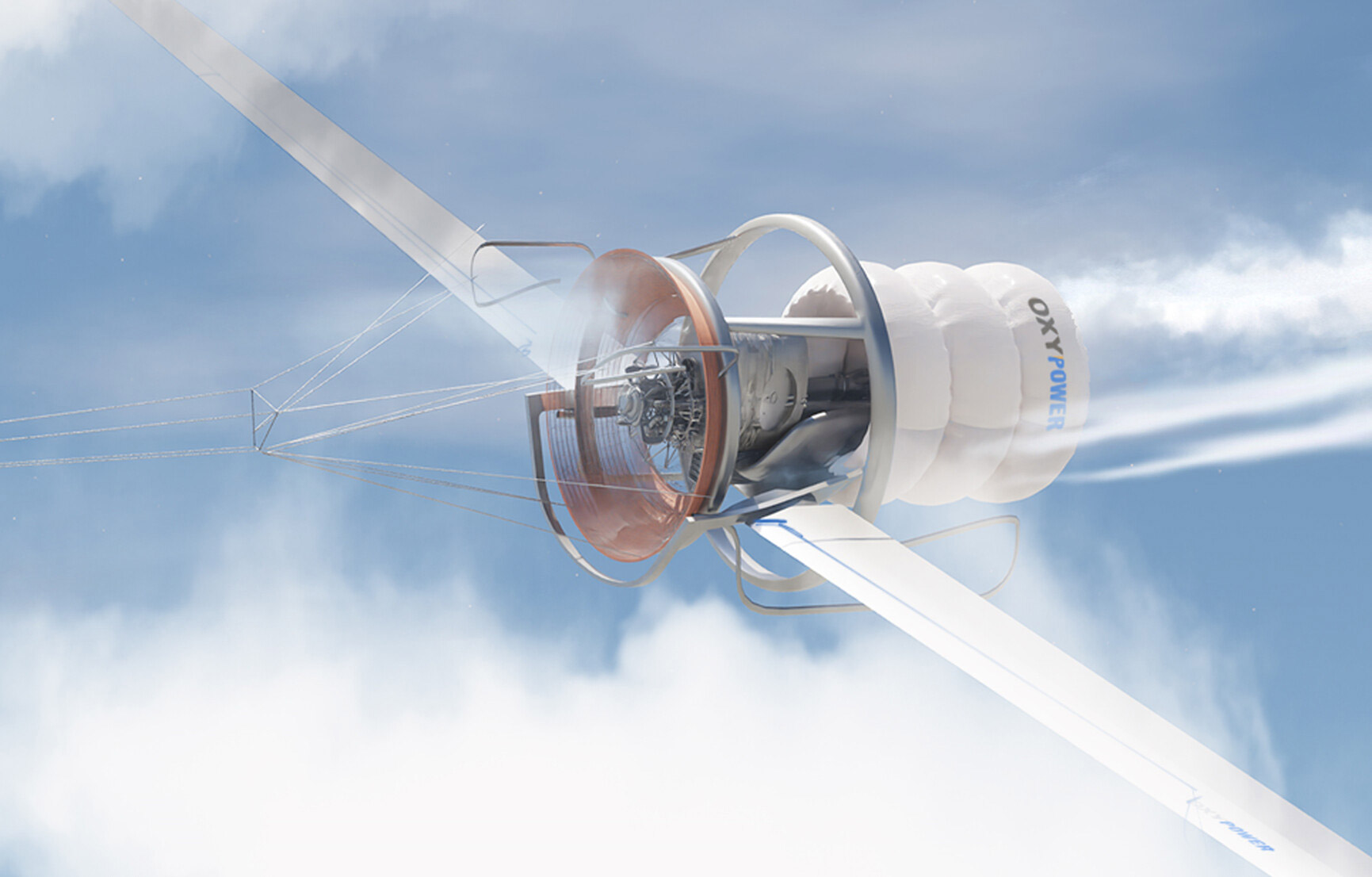

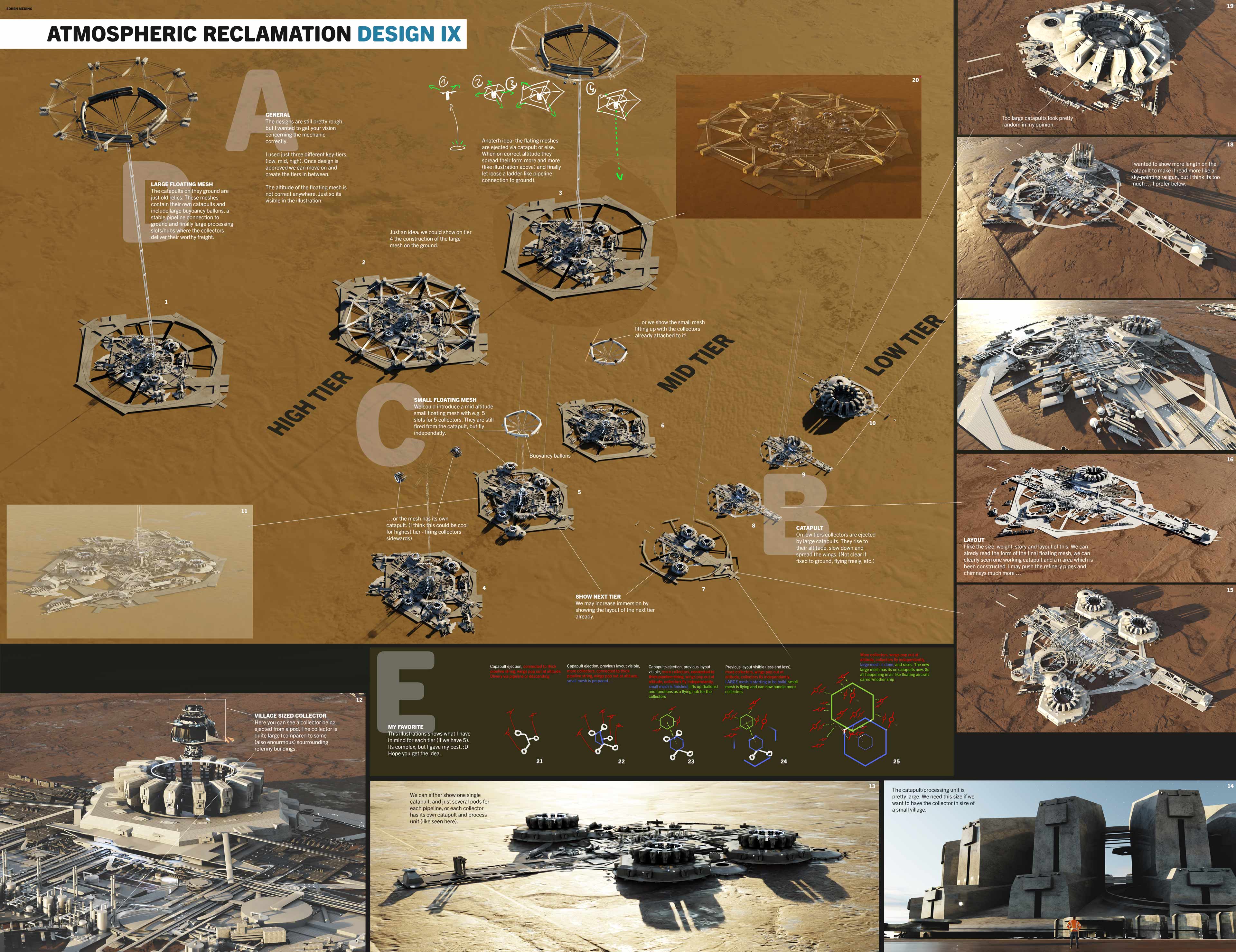

The first step was assembling a rough, lightweight kitbash library, just enough to start experimenting in the sandbox. This shot was one of the earliest tests, and it already looked promising. It combines a thin, lightweight scaffold-like structure, a chrome metallic extractor in the center, and a few small planes for scale. As always: immense scale.

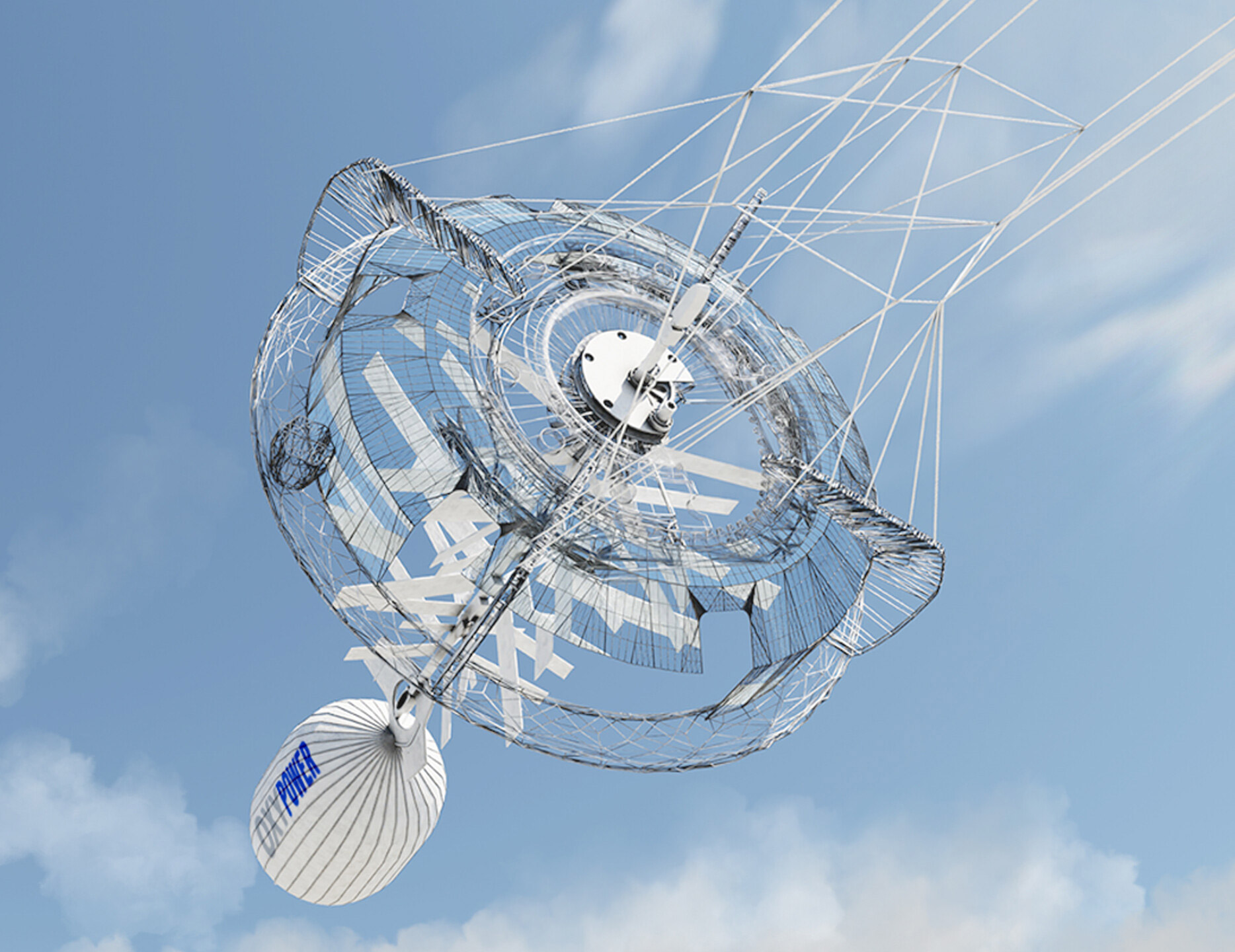

Here you can see how I worked my way along the initial sketches, exploring a wide range of design directions. The 3D process sparked even more ideas, resulting in a large volume of concepts. But a word of caution: for a client, this can easily become overwhelming. It’s often better to art-direct yourself early on and narrow things down, presenting only 3 to 5 focused concepts rather than everything.

Iteration Explosion: An Honest Post-Mortem

Looking back, I sent all of the ideas to the client. Back then, I struggled to art-direct myself.

There were just too many images. And if you assume an art director only has 3 minutes to review your work, there’s no way they can fully digest your thinking. Which is sad regarding your invested time.

If I could go back, I’d do it differently:

– Focus on 3–5 strong, unique concepts—clearly presented, with short supporting notes.

The classic “Artpile dump” helps no one. But maybe you’ve felt the same urge? That quiet need to say:

“Look, I worked hard, look what I painted, Dad! Please like it.”

These days, I understand: You’re not hired to show everything you painted. You’re hired to solve a problem. To tell the story. To think it through—start to finish. No one else will do it for you.

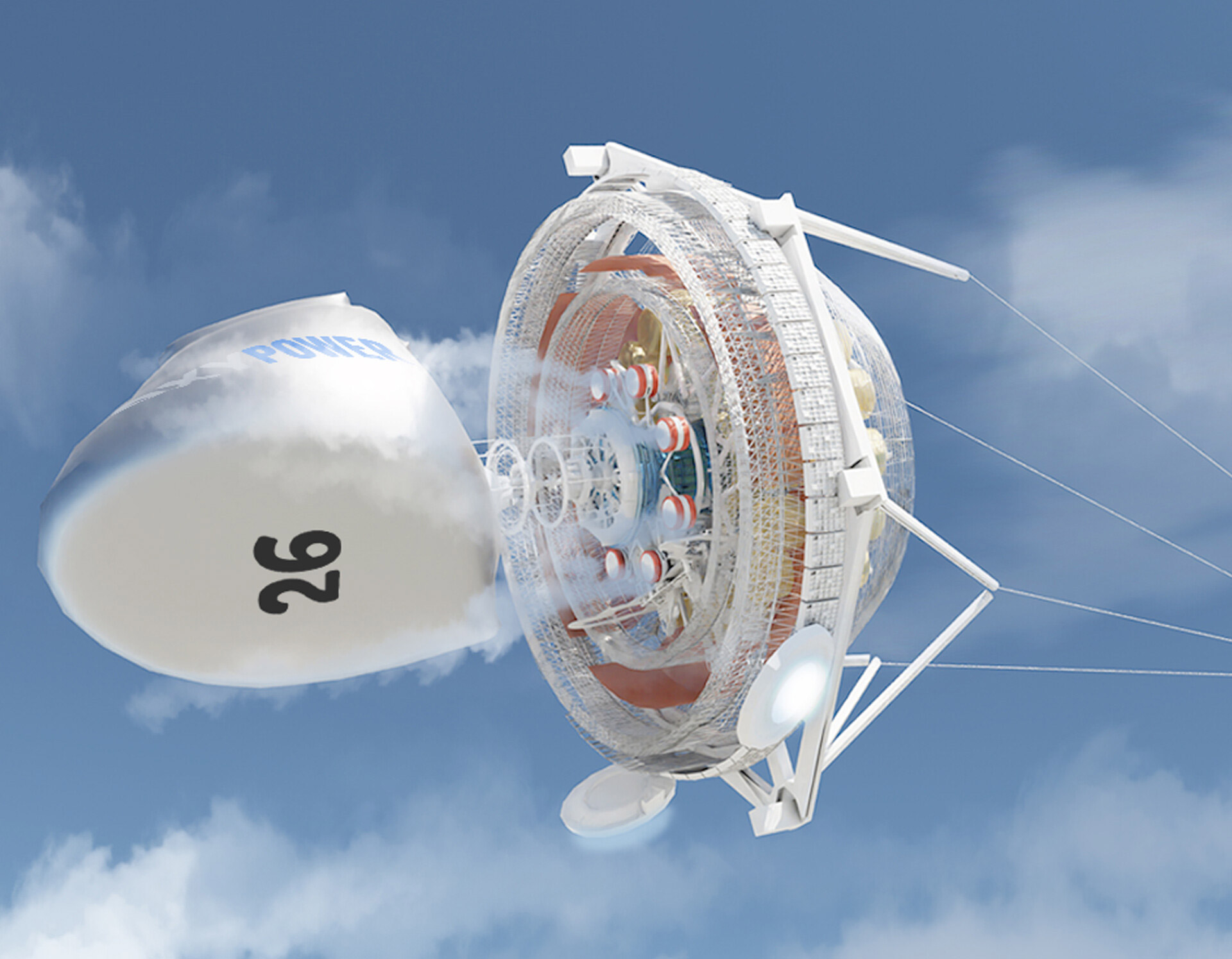

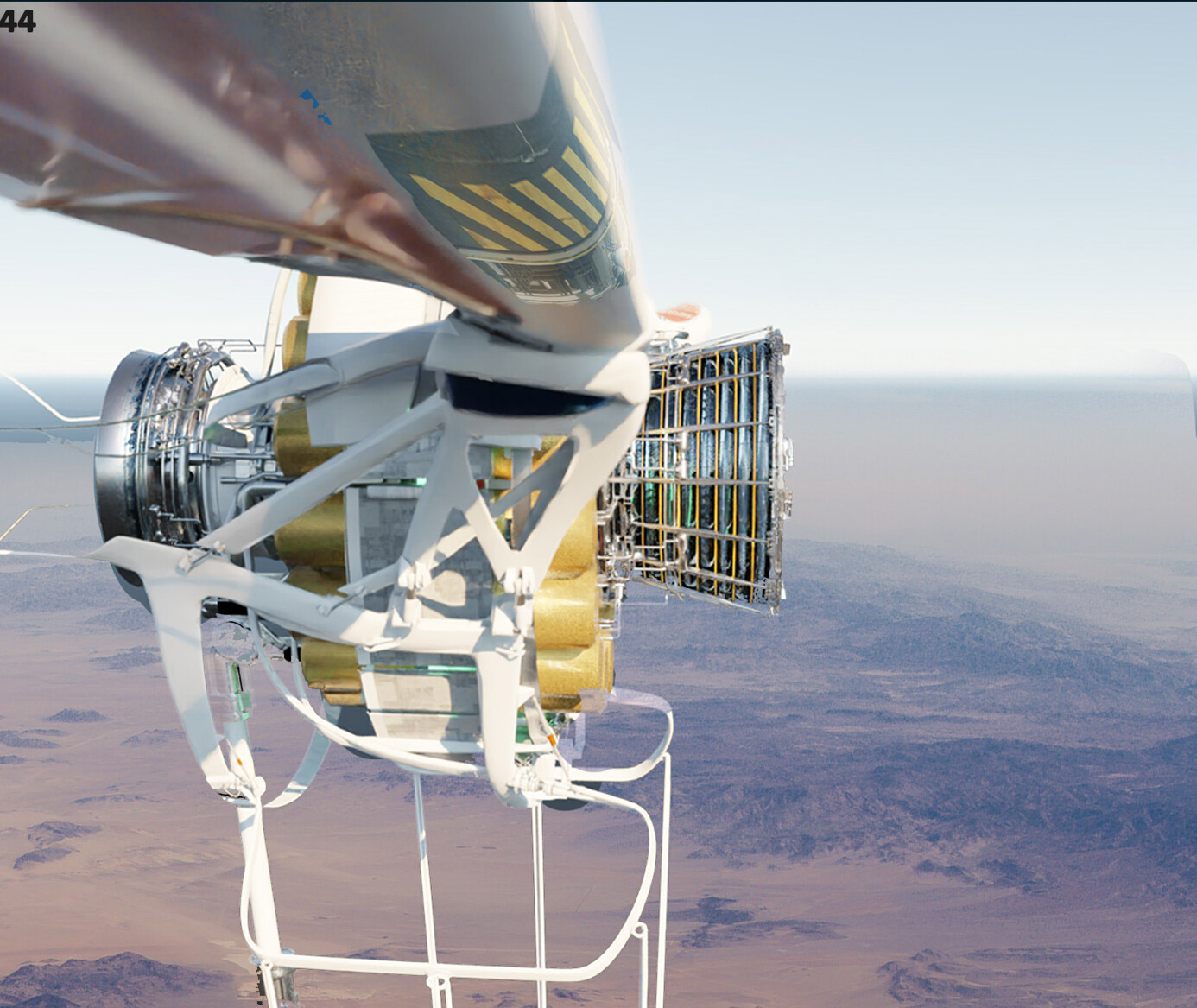

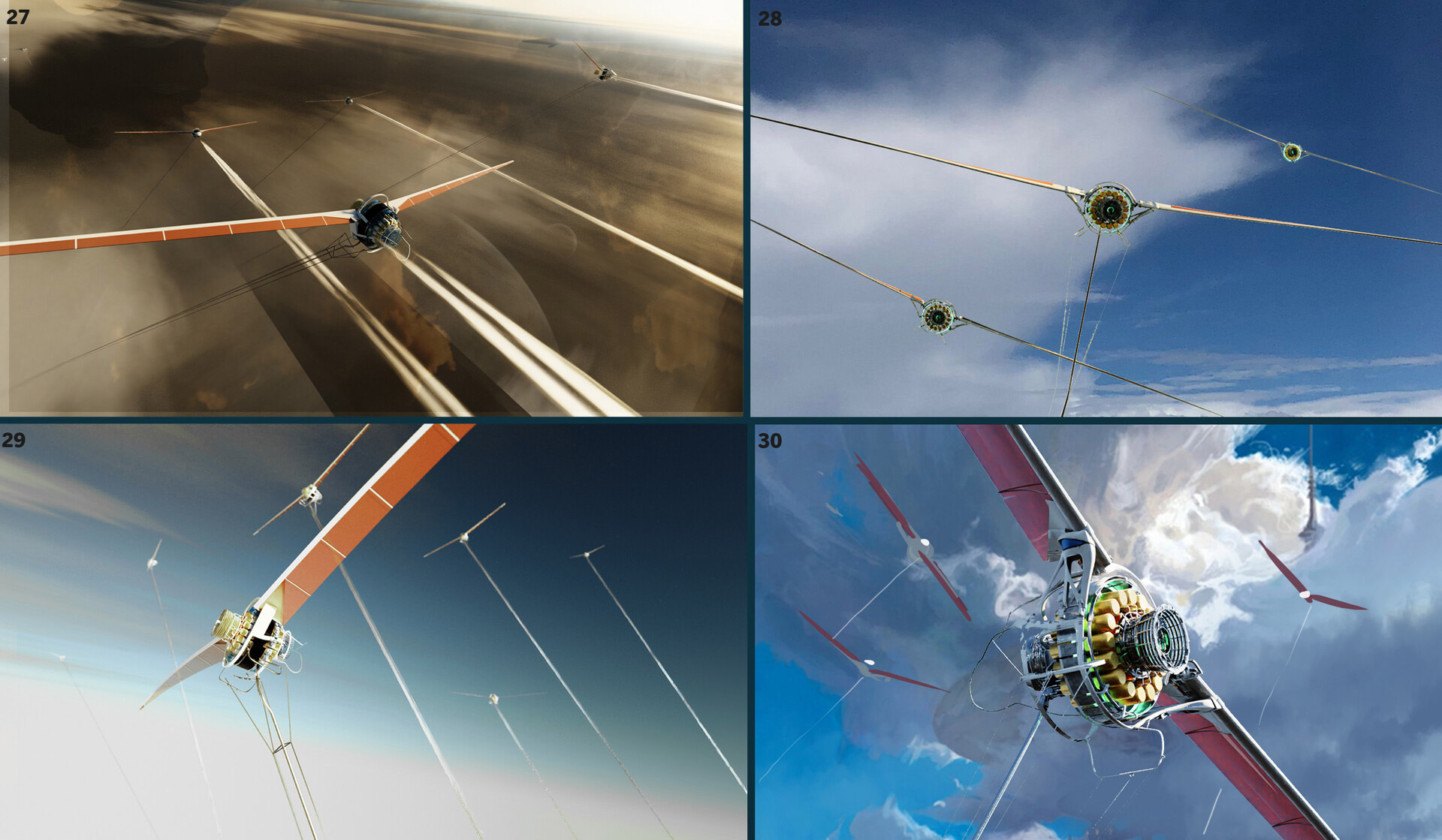

We decided to move forward with the kite–ventilator design. I created several additional callouts based on that direction. Some of which can be seen in more detail below. I also decided to add wings after all, mostly because I really love birds. These units are meant to remain stable and airborne even in the extreme storm conditions of other planets, gracefully sailing through turbulent skies.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

How does this thing actually take off?

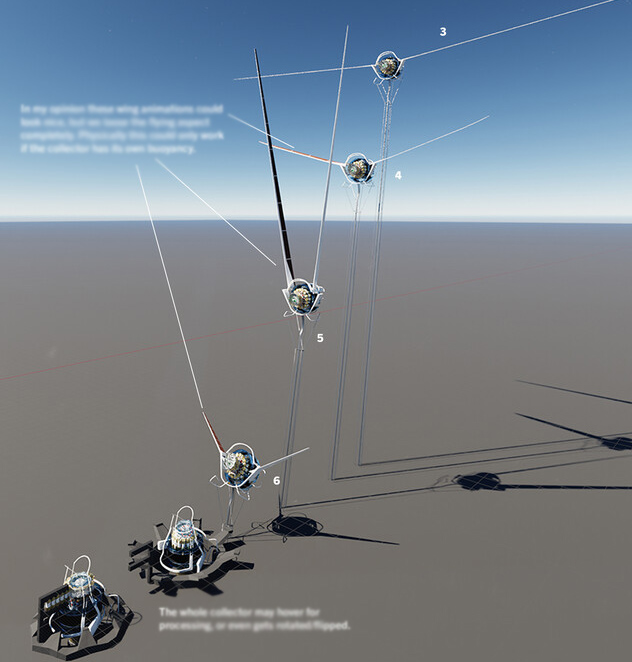

Where is it connected to the ground? To answer those questions, we needed a base structure. I came up with a tiered system, with multiple levels and varying numbers of kites. The launch itself should feel similar to a mortar or catapult, the core module is shot high into the sky like a rocket. Once airborne, the wings unfold, transitioning the unit into a steady gliding or hovering flight mode.

Base station, with refinery and catapult silos.

Adding a bit more environment and lighting to the scene. On the right: a quick mockup of a launch. After all, the Atmospheric Reclamation Unit is roughly the size of a small village.

Here are a few of the previous callouts shown in larger format. Note the automated drones in #2 and #6, they transport the filled gas canisters back down to the planet’s surface.

Here are two gameplay visualizations, not actual gameplay, just the ideas for it.